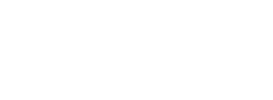

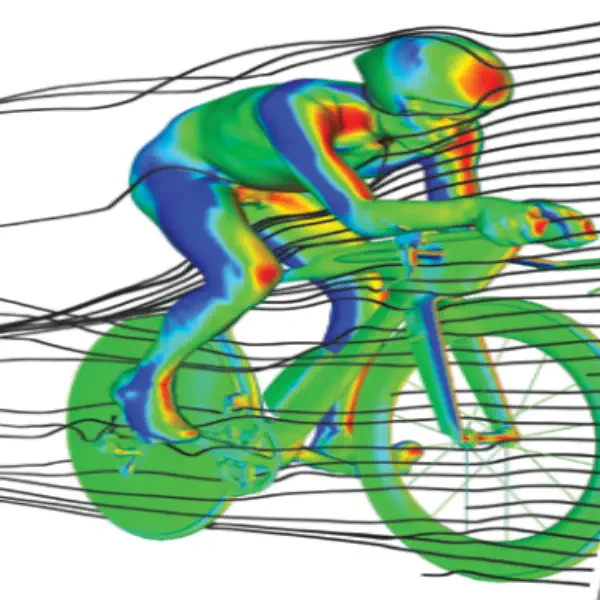

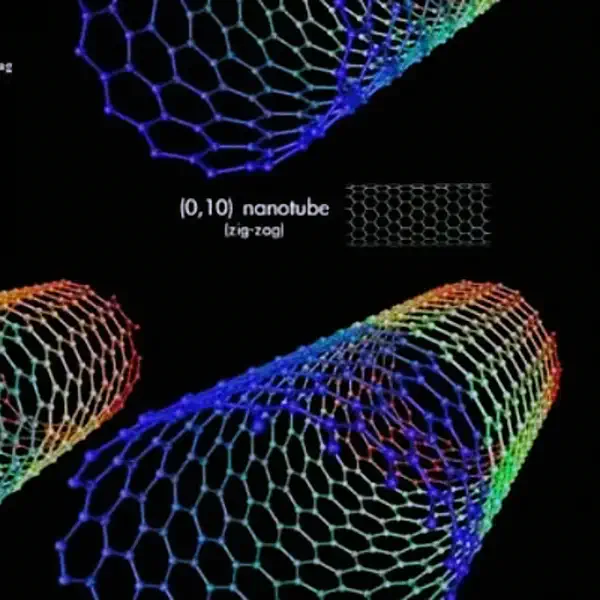

The aerodynamic versus lightweight frame design debate has entered a new phase. Modern manufacturing technologies—high-modulus carbon fiber, CFD-driven optimisation, and integrated component design—have enabled a generation of bikes that deliver both low weight and low drag, challenging the historical trade-off between climbing and aero performance.

Flagship models like the Pinarello Dogma F14, Canyon Aeroad CFR, and Trek Madone Gen 8 represent this convergence, offering complete framesets under 1,500 grams with aerodynamic efficiency rivalling dedicated time trial bikes. For most riders and most race scenarios—particularly the rolling, mixed-terrain stages that dominate professional road racing—these aero all-rounders offer optimal performance.

However, the debate is not entirely settled. On extreme gradients above 7%, where speeds drop below 18 km/h, pure lightweight frames still offer measurable advantages. And for amateur riders, the marginal gains from aero optimisation may be less significant than improvements in position, training, or tire selection.

Ultimately, the "ideal" frame design depends on specific use cases, rider strengths, and race demands. What is clear is that the binary choice of the past—aero or lightweight—has evolved into a nuanced spectrum, with modern bikes occupying a sweet spot that would have seemed impossible just a decade ago. As materials science and manufacturing continue to advance, the convergence will likely accelerate, rendering the old debate increasingly obsolete.

The future of performance cycling is not aero versus lightweight—it is aero and lightweight, integrated seamlessly into versatile machines that perform across all terrain.